By Jagatbandhu John Gross, Ph.D.

“The first thing that must be done to increase the purchasing capacity of the common people is to maximize the production of essential commodities … “(P.R. Sarkar, “Some Specialities of Prout’s Economic System”, June 1979, Calcutta). Purchasing Capacity or Purchasing Power is Prout’s basic outcome measure. It is an indicator of the ability of individuals or families to acquire economic goods and services.

Prout encourages growth in minimum necessities (MN) and overall standard of living. So, in a healthy Prout economy Purchasing Capacity will be increasing.

Purchasing Capacity is not the only economic indicator needed. Measures of sustainability and productivity as well as more traditional economic indicators will be necessary in order to understand how the economy and society are progressing.

Almost anything can be measured in a broad array of possible units, but chosen measurement units imposes no limitation on what is true in the present nor on that to which society can aspire.

An initial task for a Prout economy is defining minimum necessities for its people. Considerable variation in the defined MNs will be necessary both across and within regions. These calculations will be challenging, but a vital first step for any Prout economy.

Once MN definitions are available, our Purchasing Capacity Index (PCI) is computed in these terms. So, our proposed PCI can only be computed after clear and specific MN definitions exist.

A Purchasing Capacity Index

The PCI works as follows: If an individual’s PCI is 1.0, she is able to obtain exactly her MN as defined by Prout, but if she does this, she can acquire nothing else. Nothing will remain for luxuries, savings or any extras whatsoever. A PCI of 1.0 is the Prout poverty line, and perhaps provides a lower bound on a minimum wage. A society with a significant proportion of members with PCIs below 1.0 is failing in a basic duty.

An individual with a PCI of 2.0 would have sufficient resources to obtain her MN twice. The index is not an indicator of how Purchasing Capacity is or should be used. It only indicates available purchasing power, denominated in MN units. A PCI of 2.0 only indicates that she could easily acquire her MN with considerable resources to spare.

Why index the PCI on MNs and not on monetary units?

One reason for using a MN denominated PCI is that Prout encourages in-kind compensation. Goods and services may be a sizable portion of compensation for many Prout citizens. A monetarily based PCI would require computation of the cash value of all such compensation.

A second reason for a PCI computed in MN terms lies in easy comparison. As noted, different people and different regions will have different MNs. By computing each person’s PCI according to their applicable MN, comparison is immediately possible without the need for conversion.

The most important reason for computing the PCI in MN terms, however, is that by indexing the PCI to MN we have an instantaneous read on how well Prout is doing with respect to providing minimum necessities. Any shortfall is instantly obvious. Excessive inequality also is easily seen and it should be clear when a rescaling of the definitions of MN is due.

Economic indicators are often reported as a single number, but in Part One of this article in the last newsletter edition, we saw that such single number measures of income hide distributional information. The same is true of a PCI.

PCI data are best reported as a distribution. There are a number of ways to do this. For reporting to the public, easy to understand bar graphs are probably best. Policy makers and academics will need complete and thus more finely granulated data so the same distributional data should be made available in complete form for anyone, but for the same reason that most individuals don’t currently download publicly available detailed economic data, such complete data will probably not be of general interest.

We motived our lasix 40mg proposed PCI as a measure for a Prout economy, but if we compute MNs for any economy we can then compute the relevant PCIs. Defining MNs within a capitalist economy may prove challenging, but it is a worthwhile effort and once completed, the necessary data to compute PCIs almost surely already exist in some localities.

Defining MN definitions for any economy or locality is a significant effort and should be undertaken by a group of Prout researchers, rather than any individual. As this has not yet been done we cannot provide actual PCI distributions but below we show three hypothetical PCI distributions to give a sense of what these data might show.

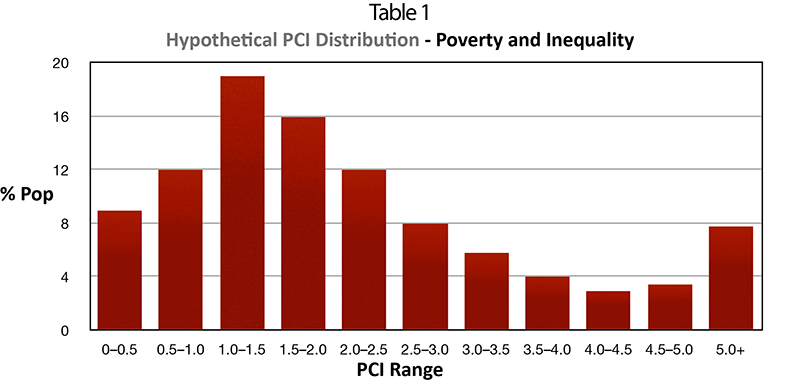

Table 1, labeled “Poverty and Inequality” shows, as indicated in the title, the PCI distribution for a hypothetical society that is far from ideal. Over 20% of the population is incapable of obtaining its MN. The last category, 6.0+ may include those whose PCIs are in the hundreds of thousands or even millions, as it probably would if these were data for a capitalist economy. To know the extent of inequality we would need the more complete data mentioned earlier.

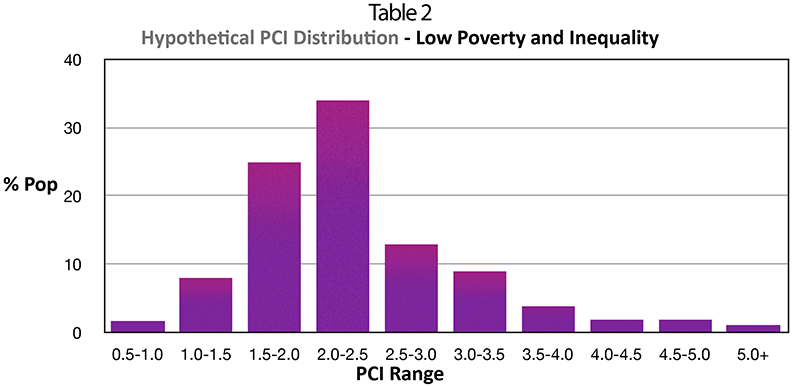

Table 2 shows a hypothetical PCI distribution for a society with only moderate poverty and some inequality. Inequality to some degree is not only to be expected in a Prout economy, but encouraged as appropriately applied economic incentives are a fundamental element of Prout. One of our Prout Economists, Mayatiita (Mark Friedman, Ph.D.) has done some work on optimal inequality (“Living Wage and Optimal Inequalityin a Sarkarian Framework”, Friedman, Mark, Review of Social Economy, VOL. LXVI, No. 1, March 2008).

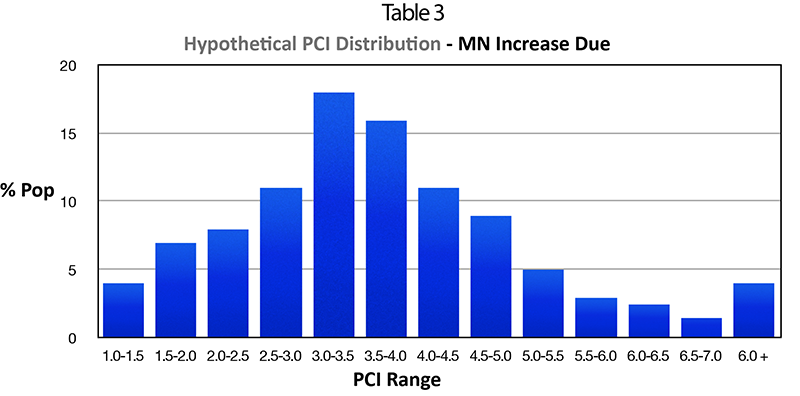

Consider the hypothetical society whose PCI distribution is shown in Table 3, labeled “MN Increase Due.” In the fictional economy represented in this table no one has a PCI below 1.0 and 96% of this population has a PCI of 1.5 or greater and 89% have a PCI of 2.0 or greater. This society has the resources to increase its definitions of MN and should do so as soon as possible.

The PCI proposed here is relatively easy to compute, is easy to compare across regions and time (though lack of space prevents discussion of intertemporal comparisons) and is grounded in basic Prout principles. It easily provides the most fundamental answers we need about any Prout economy. Specifically: 1. Are societies members currently able to obtain minimum necessities? 2. What is the overall standard of living and how are consumption resources distributed? 3. How does the standard of living vary from region to region and over time?

Jagatbandhu (John Gross, Ph.D.) is an economist and long time Proutist living in central North Carolina. His interest in PROUT inspired him to obtain graduate training in economics.